Antique Furniture Manufacturing

One of the most frequently asked questions about a piece of older and antique furniture is, “Who made it?” That seems to be a reasonable question, along with the other basic inquiries of “How old is it?” and “What is it worth?” But that first question is almost always the most difficult to answer and sometimes it is totally impossible.

The vast majority of furniture craftsmen in the 18th and 19th centuries did not mark their work. Sure there are some notable exceptions, many of which are detailed in the excellent book “American Cabinetmakers, Marked American Furniture 1640-1940” by William Ketchum, published by Crown. But even that comprehensive work is less than 400 pages in length to cover a period of roughly 300 years.

How is it then that so much American furniture, especially that of the 19th and 20th century, is unmarked? The answer lies in a term currently in vogue for shipping work elsewhere: outsourcing. We tend to think of this as a modern manufacturing occurrence, but it has been a common practice in the furniture industry for more than 100 years.

One area of manufacturing even has a special name for it and it is still in practice today, although it is not so widespread as it once was. The piano industry, especially early in the 20th century, employed a practice called “stenciling.” This happened when a major manufacturer such as Kimball or Everett or any one of the big plants agreed to produce a limited number of pianos that carried the name of a special customer rather than the name of the piano maker. The special customer may have been a major department store such as Macy’s or even a particularly important dealer or a special individual customer. Probably the largest beneficiary of “stenciling” was Sears and Roebuck, selling mail-order pianos they had never even seen.

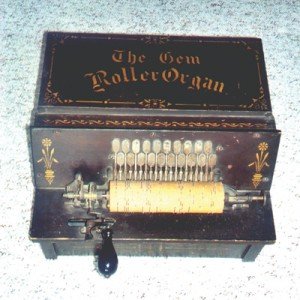

A popular musical instrument of the early 20th century was the “Gem Roller Organ.” It was a sort of hand-operated music box with roller “cobs” that produced the tune. In the 1902

Sears catalog, it was touted as “Our Gem Roller Organ” for the price of $3.25, a price reduction from the previous catalog’s price of $4.25 that “was made possible by our contracting for the entire output of the factory which makes this wonderful little instrument.” That was the way Sears worked. In the front of the catalog, the process was openly explained. “We are able to make contracts with representative manufacturers and importers for such large quantities of merchandise that we can secure the lowest possible prices.” Sound familiar? That’s why it is impossible to absolutely identify the maker of the turn of the century Sears china cabinet other than to say for sure that it wasn’t Sears.

Another major area of outsourcing was also in the music industry: cabinet works for various phonograph styles. The cabinets evolved as the phonographs evolved but seldom will you see a cabinetmaker’s name on a Victrola or Edison cabinet. You just assume that Edison or Victrola had its own factory to make the cabinets. Not quite. One example was the Udell Workshop in Indianapolis. Udell was a major maker of early Arts and Crafts furniture and also produced some credible Colonial Revival furniture in the Depression era, but it was best known for making the cabinets for the table model Victrola and Columbia turntables of the early 1920s.

As an aside but still on the subject, one of the largest “independent” brands of talking machines was the Standard Disc Model A sold by the Standard Talking Machine Co. of Chicago. It was made from top to bottom by Columbia with a Standard label.

A variation on the theme was Thomas Alva Edison’s approach In 1917, Edison purchased Wisconsin Panel and Cabinet Co., a maker of opera seats that had been incorporated a year or so earlier in New London, Wis. Edison converted the factory to the production of cabinets for his newly patented line of phonographs. Edison Wood Products made phonograph cabinets until 1927. Demand for phonographs waned during the Depression, so to preserve the employment of several hundred employees, Edison decided that the company should make juvenile furniture under the trade name “Edison Little Folks Furniture.” That line has survived as a part of Simmons Juvenile Products. Several major Grand Rapids, Mich., factories also made cabinets for the phonograph industry, but you will almost never find their label on one.

Still another variation that makes positive identification difficult came from the furniture industry in Grand Rapids. During the Depression in 1931, nine manufacturers formed the Grand Rapids Furniture Makers Guild (see Antique Trader, Sept. 19, 2012). The formation of the guild allowed the companies to collaborate to gain an advantage over individual competitor companies. They established a network of “guild dealers” who sold only or mostly products from the guild. These products were identified by the brass tag of the guild but most often did not carry the name of the specific company that made the furniture .